Partager par e-mail

Téléchargement de documents

didid.pdf

11.2mb

11.2mb

Télécharger le succès

Information essentielle

Académique

Le téléchargement a réussi, soumis à l'audit

Le résultat de l'audit devrait être de 2 à 3 jours. Les documents de révision seront affichés publiquement

Il n'y a pas assez de pièces à télécharger

Ce document nécessite5pièces pour télécharger

Utiliser pour le téléchargement

Partager par e-mail

/fr/share/9/whats-next-social-media-trends-2020.html

COPIE

Document de rapport

Le document et les utilisateurs signalés sont examinés par Speedpdf staff 24 heures sur 24, 7 jours sur 7 pour déterminer s'ils enfreignent le règlement de la communauté Les comptes sont pénalisés pour violation du règlement de la communauté et des violations graves ou répétées peuvent entraîner la résiliation du compte Canal de rapport

Désolé, notre service de conversion ne prend pas en charge votre navigateur actuel!

Il est recommandé d'installer Google Chrome, puis de revenir sur pour utiliser le service de conversion de documents. Je vous remercie.

Accédez à Chrome

PARTAGER

PARTAGER

This year, on the eve of Holi (also known as Holi, which is also the traditional Indian New Year), 10 men holding cardboard statues gathered outside a jewelry store in the northern Indian city of Kanpur. These cardboard statues are five feet tall, have pink heads and curly beards on their faces. According to local festival customs, these statues are made for burning. On the torso of the statue, these people nailed an image of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

This is a live demonstration organized by Praveen Khandelwal. Khandelwal is a Delhi businessman who leads a chamber of commerce of about 80 million small business owners: the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT).

When the group of businessmen in Kanpur prepared the portrait of Bezos, hundreds of Indian businessmen scattered across the country appeared on Zoom (participating in online demonstrations). They were supposed to show up offline for activities, but India is in the deadly second wave of the epidemic, and cities across the country are already under lockdown. These merchants make video calls in their own shops, on balconies and terraces, or just standing on the street. Many people have homemade cardboard statues of the world's richest man: a shopkeeper and his two children holding Bezos's profile picture and the silhouette of the multi-headed demon Ravana with the "AMAZON" logo on his chest appear on Zoom.

Khandelwal gave an order and they burned their images of Bezos. During the Holi festival, the burning of the statue represents the elimination of the female devil Holika, which is an annual victory of justice over evil. For shopkeepers and businessmen, Bezos is the demon to burn this year.

This gimmick is Khandelwal's latest gameplay. The 60-year-old businessman has a deep relationship with Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). As the leader of CAIT, he has been in the public for more than 30 years. Khandelwal and businessmen like him are the foundation of Moroccan government. They represent the support of India, the local economy that Modi likes to boast in his speeches. However, the blockade caused by the epidemic has destroyed physical companies in India, allowing foreign e-commerce platforms such as Amazon to seize the opportunity to enter the eyes of more than 1 billion consumers in India.

As more and more Indians turn to Amazon (its 90 million online shoppers are estimated to quadruple by 2025) and similar e-commerce platforms, Khandelwal's fans are pushing the Prime Minister to face the "Bezos" of the world. The act of opening a shop on its site takes a firmer stand. Khandelwal even launched a trader-friendly e-commerce platform, aptly named Bharat E Market, or "E Market in India", trying to get a share of the network economy.

When the mannequin began to burn and plumes of smoke appeared on the screen, the sellers in the Zoom video began to shout in unison, "Amazon, go back!" Here we borrowed the slogan of India's boycott of Britain during the colonial period.

"Why are we burning their portraits?" Khandelwal yelled into his computer camera. "We decided to burn the images of Amazon and Flipkart on Holi, showing that India's laws are not weak, and the Indian government is not weak." The businessmen cheered in unison. "You make this a problem in every village and every town, so all of our talents have come together."

1. Bezos's Indian courtesy

One night in December 2019, when Khandelwal was browsing the web on his iPhone, he saw headlines about Jeff Bezos' visit to India. Although he has built a reputation for fighting for the interests of small businesses since the 1990s, since India's relaxation of foreign investment laws in 2016, Amazon has begun to dilute the interests of the alliance of small business owners, and Khandelwal regards Amazon as its biggest rival.

At that time, Bezos will meet with the prime minister and senior cabinet members. This is Amazon's fourth visit to the country since it established a center in India in 2004. "During his last visit (2014), he was welcomed by the red carpet of the Prime Minister's Office." Khandelwal exclaimed, vowing to prevent Bezos from continuing to receive the same courtesy.

Whenever Khandelwal came up with a propaganda technique, his round face with a beard would smile, and his speech speed was confusingly fast, and only slowed down when he switched to English. He is a rich man. There is a hardware wholesale store on one of the busiest streets in Delhi. He drives a maroon Jaguar to attend many political and business meetings. Khandelwal with an emerald ring on his little finger and a stack of cash in the inner pocket of his trousers is a typical image of Lala ji, a traditional Indian businessman.

In his office in the family store, dozens of framed photos hung on the bright yellow walls, including a black and white portrait of three generations of Khandelwal family merchants dressed in prince costumes. On the opposite wall, there is a 3-foot-tall collage with Khandelwal sitting with Prime Minister Modi, and both of them are laughing. Khandelwal’s family devoutly supports Modi’s BJP, partly because the prime minister also supports businessmen like them.

Since coming to power in 2014, Modi has made it clear that India is open to business. In the first column he wrote for The Wall Street Journal after taking office, he wrote: “India will be open and friendly towards business, creativity, research, innovation and travel.” As the chief minister of Gujarat, India, he has been for many years. He has cultivated a reputation for being business-friendly, and at this point he has the support of Indians at home and abroad who are eager to improve the country’s international status.

Although Modi advocated that India be open to foreign business and innovation in his campaign, he also advocated the idea of putting Indian companies first. Soon after taking office, the Modi government promulgated the "Made in India" campaign, which aims to promote India to become a global manufacturing leader by relaxing certain foreign investment regulations. In many ways, India’s move to open its borders to foreign investors has played a role. The inflow of foreign capital into the country has reached a record high. He kicked off the 2019 election campaign with the promise of a "New India". Modi declared that this "New India" would be "consistent with its glorious past", promising economic growth and national prosperity.

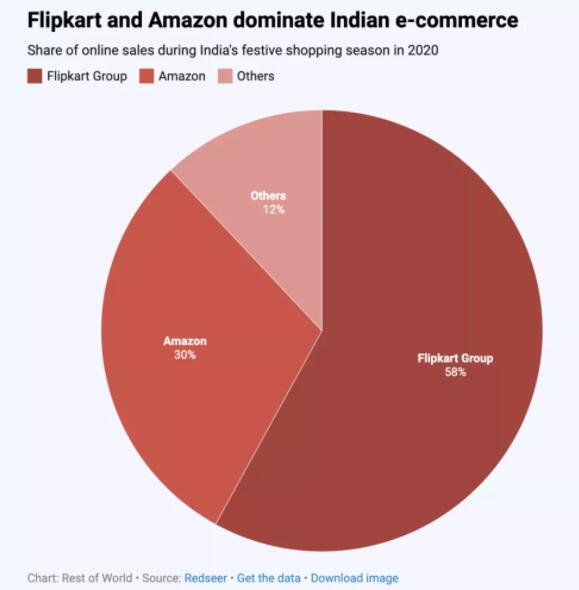

In order to boost the weak economy, the Indian government is conducting the largest privatization operation in more than a decade, selling its positions in major state-owned enterprises. Although small businesses are struggling with a bleak economic outlook, the combined market share of Amazon and Wal-Mart’s Flipkart has grown substantially. The prolonged lockdown has further consolidated Amazon's position: Since the epidemic, Amazon's sales have doubled.

Online sales share/mapping for the Indian holiday shopping season in 2020

Bezos' second trip to India was shortly after Modi took office and one year after the e-commerce giant fully entered the Indian market. Not long before the visit, Bezos announced that he would invest US$2 billion in India to develop India's national business and met with him in Modi's office. Modi posted a photo of the meeting on Twitter, and the two of them smiled at each other.

Although Bezos was warmly welcomed, India has safeguards to prevent Amazon and other e-commerce companies from taking over the Indian commercial market. In the United States, Amazon can sell its own inventory directly to customers on its platform, while Indian legal restrictions restrict this. This restriction is to protect small businesses. This means that Amazon can only be used as a platform to collect fees from Indian suppliers to display products, and cannot directly establish exclusive deals with manufacturers to create Amazon-branded products.

But Amazon has bypassed these restrictions by creating its own Indian seller entity, the most prominent of which is called Cloudtail. Founded in 2014, Cloudtail is a subsidiary of a Bangalore company called Prione Business Services. It is a joint venture between Amazon Asia and an Indian venture capital firm founded by Infosys founder N.R. Narayana Murthy.

This year, a Reuters survey found that clever techniques like Cloudtail have enabled Amazon to flourish in India. Although the country's Amazon platform is crowded with hundreds of thousands of sellers, large and small, as of the beginning of 2019, about 35 merchants accounted for more than two-thirds of Amazon's online sales, benefiting Amazon and large-scale commercial activities.

Amazon's continued circumvention of Indian legislation angered Khandelwal. "These companies have been selling all year round, giving unimaginable discounts. They are blatantly flouting policies and laws." He told the media.

Second, the counterattack of small merchants

In 2018, the Modi government announced further restrictions on e-commerce to prevent the expansion of large platforms. These rules specifically target foreign e-commerce companies such as Amazon and Flipkart and prevent them from owning more than 25% of seller entities such as Cloudtail. For Modi, the timing of the rule is crucial: he is working for re-election, and for the Bharatiya Janata Party, small businessmen like Khandelwal constitute a strong support, and he cannot be alienated.

This pacified the small vendors and Khandelwal, forcing Amazon to sell some of its shares in the two seller entities, and caused a temporary failure, because some products, including the Amazon brand, are temporarily unavailable on the Indian version of the platform. By the time Bezos announced his visit in January 2020, his company's position in India had changed a lot.

Therefore, at 5 o'clock in the morning on the second day after learning of Bezos' visit, Khandelwal began to act. He sent a message to the attachés in the prime minister’s office, telling them that Bezos’ visit caused misunderstandings among small businesses, which are being destroyed by Amazon.

He sent an email to Modi's office using union letterhead, and he later shared the letter with the media. "Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is eager to meet with the prime minister (sic), definitely to cover up unfair business activities in e-commerce."

"We not only sent that letter to the Prime Minister, but also to the Chairman of the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Minister of Interior, the Minister of Defense, and the Minister of Finance." Khandelwal recalled. Soon, the ministers' calls came in. The local media reported the story. By 9 am, almost all important political functions in the Bharatiya Janata Party government had received a letter from Khandelwal's trade lobby urging them not to meet with Bezos.

Lobbying worked. During the three-day itinerary in January 2020, Bezos did not meet with any minister or government official, and Modi’s office is said to have refused the appointment. Khandelwal and CAIT redoubled their efforts and arranged a protest near the Delhi venue where Bezos spoke. When the CEO of the tech company wearing a blue sherwani (high-necked long coat worn by Indian men) bowed his hands to the crowded auditorium, Khandelwal and dozens of retailers chanted "Amazon, go back!" Khandelwal raised his fist. , Use the microphone to take the lead in talking.

Compared with Bezos' previous visit, this reception has changed significantly. Both the red carpet and Modi's tweets disappeared. This time, Indian Minister of Commerce Piyush Goyal publicly attacked Bezos's $1 billion pledge to help small business businessmen.

Soon after Bezos left the country, the Secretary of Commerce met with Khandelwal.

3. The path of inferiority and autism of the right-wing populist government

In the early 20th century, the Khandelwal family started their trade in Delhi and made a fortune by selling construction hardware. After the partition of India, the country's economy was largely isolated from the global market, and their business started with almost no imported products. Khandelwal said: "People in our family used to import everything including playing cards and key chains, because these things were not produced in India at the time."

Khandelwal is a political performer, which has won him the favor of the local media, who are always eager for his colorful comments. He has become a regular topic figure on TV. Burning the remains and sitting in is the main part of his rules of the game; so is his Twitter, which conveys endless contempt for e-commerce. But he has something to do with him. In a country where his backer and ancestry are important, his family heritage paves the way for him.

The merchant class in India has a long history and is ruled by the Banya tribe belonging to the Vaishya caste. In the Hindu caste system, they are a social class that handles lending, banking, and commodity transactions. During the Mughal rule, the Baniyas were incorporated into the mercantile tradition.

The historian Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi wrote: “Without their knowledge, no transaction can happen.” Over the years, the successful connection between the Bania caste and trade has made them the strongest business in India. group. Many well-known Indian business tycoons, such as the Ambani family, the Burras family, and the Jindel family, are from the Bania caste. Their personal and industrial history closely follows the development trajectory of the Indian economy and extends to the country’s Internet boom. .

Growing up, Khandelwal always knew that he would join the family business, but he never expected to be as fast as he is now. In 1975, when Khandelwal was a teenager, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (Indira Gandhi) blocked the country for a long period of time, which is now called "the Emergency". After the war with neighboring Pakistan and political tensions intensified, India fell into a 21-month suspension of constitutional rights, and Gandhi arrested thousands of political opponents.

Khandelwal’s father and uncle are the heads of their company and are also members of an emerging organization Jana Sangh, a political branch of the Hindu nationalist organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), accused of spreading the community It has been banned many times for hatred, but in recent years, the organization has repositioned itself as a right-leaning youth organization. During the "state of emergency", the organization went underground and Khandelwal's father was eventually arrested and imprisoned, spending two full years in prison.

Speaking of this period, Khandelwal still shed tears, his daily elation gave way to the fragile memories of his youth. Khandelwal remembered visiting his father in prison once, and his father told him: "Although you are still a child, you have responsibilities on your shoulders. You must go to the office regularly to help your uncle."

The businessman's politics was formed during the uncertainty during the "state of emergency", and his father's organization Jana Sangh eventually became the People's Party. Khandelwal said that his loyalty to the BJP went beyond the scope of voting. "This is from the heart. We are closely connected with ideology."

Khandelwal worked in the student department of RSS when he was a teenager, with people who later became members of Modi. Even then, he had a knack for propaganda and managed media relations for student groups, typed out press releases and passed them to the editors of media organizations.

Modi's overwhelming victory in 2014 inspired Khandelwal. The rise of the right-wing populist government coincides with his rising status as an industry leader. However, despite their common Indian nationalist ideology, Modi's desire to bring foreign investment to India caused Khandelwal to diverge in the economic policies of his own party. Khandelwal believes that welfare and attention to Indian domestic retail and trade are the way forward.

According to political scientist and writer Vinay Sitapati, Indian nationalism “has no ideological view on the economy”. Although the political doctrine of nationalism is about organizing and uniting Hindu societies and establishing a permanent voting area, Sitapati pointed out that Hindu nationalists are rather vague on issues of governance and foreign policy.

Much of India’s modern history is defined by the closed, self-reliant economic theory of the Congress Party, which has dominated India until Modi’s reign. This led to widespread social unrest and economic stagnation, which eventually led to the financial crisis of 1991, prompting India to open its borders to free trade.

Some factions of the Bharatiya Janata Party strongly opposed the reforms of the early 1990s. The ideological vacuum has led to “in the past five to six decades, the leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party have different views on the economy. And many of them are contradictory.” Sitapati said that Modi was even ascending to the post of prime minister. Before, he stood firmly in the reform camp. During his tenure as chief minister, he invited large foreign companies to establish manufacturing in Gujarat, which is often considered to have changed Gujarat. Under his leadership, today's Bharatiya Janata Party is full of enthusiasm for market-oriented economy. In addition to occasionally assuming a posture of self-reliance, Modi’s policy welcomes privatization and foreign investment.

Sitapati further pointed out that the Bharatiya Janata Party has a political consciousness from the beginning that if it is seen as an economically rather than socially right-wing party in India, it will be detrimental to winning elections. High-caste merchants like Khandelwal still exert some influence due to historical reasons, but this has not translated into protectionist policies.

Fourth, online and offline gaming

This puts Khandelwal and CAIT at the forefront of an uncomfortable battle that pits them against some of the hallmarks of Modi's economic policy. The lobby group and Khandelwal emerged in 2018, when it threatened to hold nationwide demonstrations against Wal-Mart’s $16 billion acquisition of a majority stake in Indian e-commerce giant Flipkart.

They called the transaction a “cancer” in the retail industry and lobbied regulators to review the acquisition, but Modi’s office and the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and the Competition Commission of India signed the transaction. Since the acquisition, Flipkart's users have increased from 10 million to approximately 108 million. With the expansion of Amazon and Flipkart in India, certain industries in the retail market have been particularly affected, including retailers of consumer electronics. By 2020, one out of every two mobile phones in India will be purchased online, putting brick-and-mortar retailers into trouble.

For mobile phone sellers like Arvinder Khurana, this shift is cruel. Kurana said: “Before e-commerce, I couldn’t even find time to eat. We always stood and sold things.” But after 2015, when Amazon and Flipkart began to provide exclusive smartphone models online with At large discounts, retailers like Khurana cannot compete.

"I found that the children of major customers come to the store, but do not buy mobile phones. They will check the mobile phones in my store and then order them online." Khurana said that there are 25 cheapest smartphones that are not even in the store like him. For sale in the store.

Retailers scrambled to make flash purchases online, just to get exclusive inventory. Khurana described that the shopkeepers put together more than 30 credit cards and ID cards to buy a large number of online mobile phones for their stores. But these hacks are the last fight in a system that is unfavorable to the shopkeeper.

According to data from the All India Mobile Phone Retailers Association, since 2019, more than 40,000 mobile phone stores have closed. Khurana closed its three stores and dismissed these employees. Some of them now use Uber to drive taxis, and some of them cut their hair in the hair salon. Khurana said that educated people are being driven out of the industry.

In response, the Indian authorities have begun to take action against e-commerce platforms. In January 2020, the week Bezos intends to visit India, the country's antitrust regulator launched a formal investigation into Amazon and Flipkart based on a complaint from a group of traders based in New Delhi. Khandelwal and Khurana, as well as other affected traders, said that the platform used deep discounts and exclusive cooperation to influence prices, especially in the area of mobile phone sales, and gave preferential treatment by helping specific sellers to reach deals with manufacturers.

In a media inquiry, a spokesperson for Amazon India declined to comment. In a press release in April, the company stated that more than 50,000 offline retailers and community stores are sold on Amazon India. Since January 2020, it has helped India create nearly 300,000 "direct and Indirect" employment opportunities.

Before the commission began investigating whether these exclusive cooperation violated Indian antitrust laws, Amazon challenged the decision in a court in Bangalore and the investigation was shelved. An investigation by Reuters in 2021 made offline retailers again call for further investigations. A court said that the results of the investigation confirmed the long-standing allegations against priority sellers.

After the report was published, Khandelwal called for “immediately prohibiting Amazon from operating in India” and once again called for new rules to restrict e-commerce. His appeal received media attention, but unlike his big move against Bezos, nothing else happened.

5. "Speech for the place"

In May 2020, when most parts of the world were still troubled by the impact of the epidemic on health and the supply chain, India was relatively unaffected due to the complete nationwide lockdown. Optimistic policymakers predict that a V-shaped recovery will occur under the stimulus of Modi's "India First" recovery path.

"Speech for the local" has become the slogan of the government. Modi said in a televised speech to the country: "The coronavirus crisis has made us realize the value of local manufacturing, local markets and local supply chains. Locality is not only our need, but also our responsibility."

For Khandelwal, he saw friends and neighbors turning to online shopping during the first wave of blockades. This was a call for personal action and a signal to finally resurrect his thoughts that he had been brewing for many years: to create his own local e-commerce platform. In September 2020, CAIT launched Bharat E Market (Bharat is the Sanskrit name for India). In the press release about the platform, the platform aims to "make the stores near you closer to you with just one click."

Khandelwal's definition of Bharat E Market is simple. It serves as a platform for Kiranas (the corner shop where Indian households buy most of their daily necessities) and does not charge seller commissions. On Bharat E Market, various types of merchants can create their own online stores, provide private discounts to customers, and theoretically reach a larger customer base. Khandelwal explained that users on the platform can shop from any store within 3 miles of them by simply entering their area code.

Although Khandelwal has wanted to build this platform for years, the old-school shopkeepers have been reluctant to change. "Now every businessman, every Tom, Dick and Harry, is aware of the power of e-commerce." Khandelwal said.

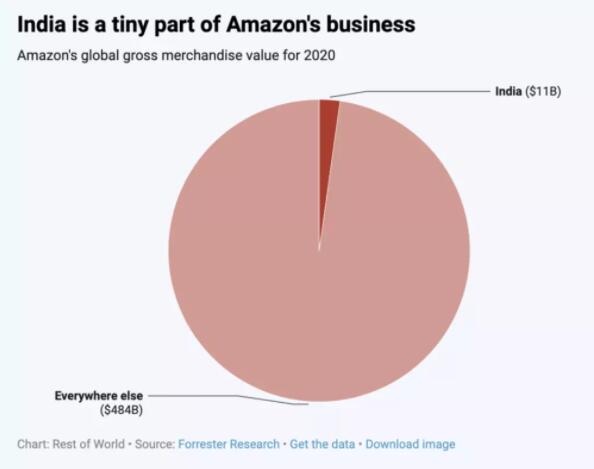

Amazon's total global product value/mapping in 2020

Amazon's 2020 global merchandise value/mapping: Rest of World; data source: Redseer

But it's hard to imagine Bharat E Market being able to compete with companies like Amazon or Flipkart, or even local competitors who have built their own platforms. The website was established by a team of five programmers in Indore, which is known for its cotton and textile industries, not programmers.

Most of the founding members of the platform are old-school businessmen in their 50s. As the head of Bharat E Market, Khandelwal's management of the website is more like a political action than an e-commerce startup. He selected 56 locally recognized businessmen and called them "e-commerce warriors" to hold seminars to train suppliers on how to register and use their platforms. He described his colleagues as “volunteers” who are “dedicated” and “honest”, which is a very Gandhian approach for a market driven by profit margins.

"These 56 people will roam in their world, arouse people's attention to Bharat E Market, and guide them to join in." Khandelwal said.

Although the growing acceptance of e-commerce has kept Khandelwal and businessmen like him on the defensive, e-commerce currently accounts for only 2% of India's retail industry. For Amazon, revenue from India is also relatively small, even when compared to other foreign markets such as Japan.

According to Forrester's data, in 2020, India will only account for 2.2% of Amazon's global merchandise value. In other words, local competitors have enough room to grow into viable competitors. Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Group and Indian industrial giant Tata Group are new entrants to e-commerce. In recent years, both companies have acquired majority stakes in key local start-ups. Amazon and Reliance Group are engaged in a high-risk court battle over the control of a US$3.4 billion Indian supermarket chain, hoping to consolidate their equity in the online retail market.

In addition to large conglomerates, hundreds of well-funded and ambitious local start-ups are helping digitize kirana stores in millions of corners. Fynd, established in 2012, is one of them. Its co-founder Harsh Shah hopes to help offline retailers sell products directly through their stores and enable them to cooperate with third-party platforms such as Amazon.

Shah, 32, graduated from the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, which is more in line with the characteristics of an e-commerce platform than Khandelwal and his cadres. Shah said that although the lockdown with the epidemic forced them to take action, traders “need to do this earlier. I think that instead of spending a lot of time questioning and opposing e-commerce and technology... A new way of operating.” Shah believes that the future of small shop owners is a mixture of online and offline sales, and large platforms “can never replicate” small shops’ acquisition of inventory and customer loyalty. Shah's Fynd is now majority owned by Reliance, which acquired 87.6% of Fynd in 2019.

Compared with startups like Fynd, Bharat E Market is a bit inferior. Khandelwal knows better what the platform is not, not what it will become. He believes that there will be no foreign investment, no Chinese products, and only Indians will devote themselves to building the platform.

Amazon’s model lists “customer first” as one of its key principles, while Bharat E Market is “for traders, (composed of) traders, and (services) for traders”. As Khandelwal said in the platform's launch video. Although Khandelwal said that 100,000 traders have signed up to the initiative, the portal has not yet become active for customers to use, and the website will be put into use in the next few months.

This left Khandelwal and the businessmen who worked with him in an unstable state. Even though he has considerable connections within the People's Party, the middle-aged businessman believes that his party can do more. "In the next six months, there will be changes." He was a little less optimistic than usual. "But of course, so far, businessmen have not received the treatment they deserve in India, even though they are providing the best for the Indian people. Service."

He is reluctant to criticize the Modi government, but the rule of the People's Party over the past seven years has left Khandelwal exhausted because he is struggling with an increasingly profitable and larger industry, and the pressure is increasing day by day. Khandelwal believes that this struggle is part of an older battle, which recalls the colonial plunder of India by the British, which plunged many of his merchant class into poverty. He still has doubts about foreigners with briefcases.

For Khandelwal, his family has firmly supported the Bharatiya Janata Party for generations, and Modi's "New India" includes businessmen like him. He regards his faith and trading business as one, and his loyalty to both blends with his loyalty to Modi himself.

Khandelwal’s WhatsApp avatar shows that he is sitting next to the prime minister, but as the country opens up its market to foreign competition, he may find that he will be the price of Modi’s new India policy.